Harvest Bible Chapel Report: Massive Corporate Governance Failure

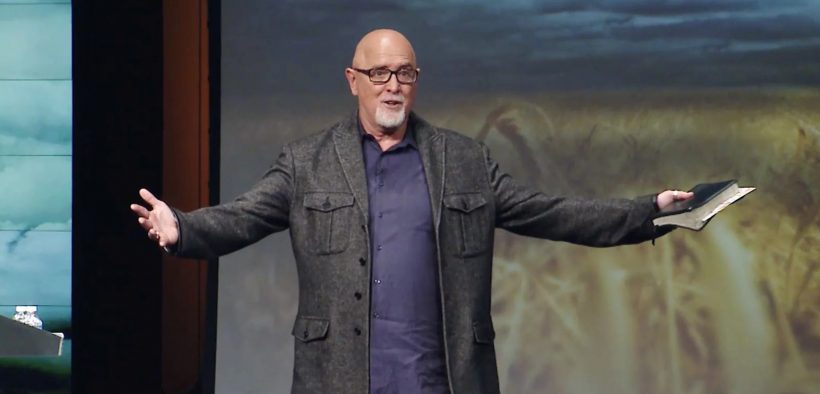

A “massive corporate governance failure apparently developed over several years” at Harvest Bible Chapel primarily because of its former senior pastor, James MacDonald, according to a report released Thursday evening (Nov. 21) by the Chicago-area megachurch.

The report by Chicago-based law firm Wagenmaker & Oberly pinned that failure on MacDonald’s “powerful and subversive leadership style,” his development of an inner circle of leaders through which he could control the church, his marginalization of the church’s elders and other leaders and other “aggressive tactics” by the former pastor.

And it’s “most glaring” when it comes to the church’s finances, according to the report.

The report comes at the request of the Harvest 2020 team of congregants, staff, elders and outside professionals formed this spring to review the church’s oversight, accountability and transparency.

That team asked Wagenmaker & Oberly to review the church’s finances and management practices to “determine what might’ve gone wrong and to put forth corrective policies and procedures to get us on the right course for the future,” according to Harvest treasurer Tim Stoner.

“It is our sincere desire to do the right thing even when it is hard, and in the process, to see the Lord repair what has been broken and to move us to a deeper and sweeter walk with Jesus. We want to follow the admonition in Micah chapter 6, verse 8, to do justly, to love kindness and to walk humbly with our God,” Stoner said.

“It is a new day,” he said.

Harvest Bible Chapel, which has seven locations across the Chicago area, has faced fallout since firing MacDonald in February for conduct its elders described at the time as “contrary and harmful to the best interests of the church.”

That included remarks MacDonald made insulting his critics, which were aired by Chicago radio host Erich “Mancow” Muller; a lawsuit (eventually dropped) against two bloggers and their wives, along with freelance reporter Julie Roys, who have all written critically about MacDonald; and years of controversy over MacDonald’s leadership style and the church’s finances.

Earlier this month, Harvest elders announced MacDonald is “biblically disqualified” from the position of elder and can never return to the church he founded decades ago as an elder or pastor.

MacDonald now is attending New Life Covenant Church in Chicago’s west side neighborhood of Humboldt Park, according to a statement he posted on Facebook last week.

In that statement, he asked for forgiveness from those who have followed his ministry and confessed “a regression into sinful patterns of fleshly anger and self pity that wounded co-workers and others.”

Despite his “repentance,” the former pastor expressed frustration with how the church has handled his departure.

“Decisions by the current Elder/staff, along with inaccurate announcements and recent public condemnation, signaled clearly the timing to communicate our message directly. With sadness we accept that no face-to-face confession or truth-advancing interaction will be forthcoming,” MacDonald wrote on behalf of himself and his wife, Kathy MacDonald.

Stoner, the church’s treasurer, and Brian Laird, chair of its elder board, shared Wagenmaker & Oberly’s findings Thursday on Harvest’s campus in suburban Elgin, Illinois.

The report described a “highly problematic culture” and “unhealthy power structure” that allowed MacDonald to “extensively” misuse the church’s finances for “improper financial benefit.”

The law firm worked with Minneapolis-based accounting firm Schechter Dokken Kanter to review two bank accounts set up in 2014 that operated outside the controls and oversight of Harvest accounting staff — an executive account and the reserve account for the church’s radio ministry Walk in the Word. Those accounts were controlled indirectly by MacDonald and directly by Harvest’s former chief financial officer, chief operating officer and an executive assistant, according to the law firm’s report.

Of the $3.1 million spent from those accounts between 2016 and MacDonald’s firing in February 2019, $1.2 was payment of deferred compensation — mostly toward retirement for MacDonald. That had been approved by Harvest’s compensation committee, according to Schechter Dokken Kanter’s separate report.

The remaining $1.9 million was used for other spending — “frequently at MacDonald’s discretion,” Stoner said.

That includes about $286,000 in direct payments to MacDonald and his family for things like an internet tower installed at the MacDonalds’ house, car repairs, college tuition and two motorcycles, he said.

“For sure, it is difficult to see how one could justify spending the church’s money on these items,” Stoner said.

There was also $94,000 spent on clothing and eyewear, mostly for MacDonald; vehicles for friends and ministry donors; a $25,000 donation to the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C.; $171,000 on hunting and fishing trips; $71,000 on a deer farm owned by Harvest in Newaygo, Michigan; and $36,000 on a private investigator, of which the treasurer said, “We’re not sure of the purpose of this expense.”

“Many of these payments may have been well intended or may have been part of a strategy of donor development that in the end raised more funds than were spent, but too often there is insufficient documentation or no documentation at all to confirm the intent of the payment, and it appears the decisions to spend these funds were made unilaterally without proper budget procedures, oversight or approvals,” he said.

“The bottom line: too few people controlled too much money without adequate checks and balances.”

Harvest plans to approach MacDonald for reimbursement of items that shouldn’t have been purchased with the church’s money by the end of the year, according to Stoner, who said elders want to give the former pastor “every opportunity to make right what has been done wrong and to make restitution to the church.”

The church has already implemented a number of the report’s recommendations: it closed those two private accounts in February and removed the elder board’s executive committee. It now has just one board with nine elders.

It also formed a new finance committee, tightened requirements for documentation for credit card purchases and started a new system that requires multiple bids on purchases.

It is evaluating other recommendations in the law firm’s report and will implement them “in the near future,” Stoner said.

And the church has asked its own questions about what went wrong, he said.

“We have discovered through many conversations that one of the reasons this environment was permitted to continue was because of our success as a church. We were growing in numbers and in giving. Many people came to Christ through this ministry. Many of us were growing in our faith, our knowledge of God’s word, and God did amazing things in people’s lives. It was exhilarating to see God at work,” Stoner said.

“But we realize now that we often preferred to focus on the good things happening, and, as a result, minimized some of the problems that, in hindsight, deserved our attention. We allowed the ends to justify the means by which those results were achieved, and this was wrong.”

This article was originally published by Religion News Service. It is reprinted here with permission.