The Rise and Fall of Allen Stanford

Editor’s Note: Last month was the 10th anniversary of the sentencing of Allen Stanford, who perpetuated one of the most notorious financial frauds of the past 50 years. Stanford and his associates used their connections in the evangelical Christian community to help perpetrate this fraud. This excerpt from Warren Cole Smith’s book Faith-Based Fraud, tells the fascinating and tragic story of Stanford’s rise and fall.

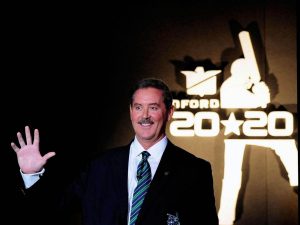

Number 205. “Two-oh-Five.” That’s what some of (former) Texas billionaire Allen Stanford’s colleagues and friends started calling him in 2008 when he was named number 205 on Forbes Magazine’s list of the 400 richest people in the world.

Soon after he was named on the list, he appeared on CNBC, the financial network. Anchor Carl Quintanilla asked him, “Is it fun being a billionaire?”

Allen Stanford, then 58, laughed and answered, “Well, uh, yes, yes. I have to say it is fun being a billionaire.”

But it got a whole lot less fun on February 17, 2009. That was when the Securities and Exchange Commission said Stanford and his accomplices had been operating a “massive Ponzi scheme,” had misappropriated billions of dollars of investors’ money, and had falsified the Stanford International Bank’s records to hide their fraud.

The SEC was blunt in its assessment: “Stanford International Bank’s financial statements, including its investment income, are fictional.” Also named in the complaint were Laura Pendergest-Holt, Stanford’s chief investment officer, and James Davis, Stanford’s chief financial officer (CFO).

The Rise of Allen Stanford

So how did Allen Stanford go from being a student at Baylor University to one of the richest men in America to one of the biggest frauds in the history of American finance? It is in some ways a classic Texas-sized story — with equal parts opportunism, hard work, and religion.

The basics of Stanford’s rise to the ranks of the super-wealthy are not so hard to follow. Stanford’s father owned a small but profitable insurance agency, and when Allen graduated from Baylor he took a job in the family business. When the oil bust of the mid-1980s crushed the Houston real estate market, Stanford swooped in, buying distressed properties, using money from his father and from friends.

By the mid-90s, Stanford had made his first hundred million, as well as many millions more for friends who invested in Stanford’s deals. Stanford began investing in real estate and other ventures in Antigua, a tax haven, and he eventually moved there. In Antigua, his massive investments and civic involvement motivated the island nation’s leaders to recommend Stanford for an honorary knighthood, which he received in 2006. After that, official communications from Stanford Financial Group and other ventures he owned would refer to him as “Sir Allen Stanford.”

Because Stanford had made so much money for so many of his friends in those early days in Texas, it was easy for Stanford to get them and others to invest in subsequent ventures.

After he moved to Antigua, Stanford grew fond of the sport of cricket. So he bought a professional cricket team, and then a league, and he changed the rules of this five-hundred-year-old, tradition-bound game. A single cricket match can sometimes go on for days. Under Stanford’s new rules, a match was less than four hours long, suitable for television. Stanford bragged in the pages of Forbes that he hoped to turn cricket into a major television sport and make himself another fortune in the process.

A “Straight Arrow”

It was just the sort of grand vision that causes excitement — and the sort of hubris that causes apprehension. So it helped that Stanford recruited his college roommate, James Davis, to be his CFO.

Davis came from the small town of Baldwyn, Mississippi, southeast of Memphis. He had a reputation as being a “straight arrow.” Jimmy Davis, as his friends called him, was a man who projected small-town values. He often opened business meetings with prayer.

The both-feet-on-the-ground reputation of Jimmy Davis calmed investors and associates of Allen Stanford, who had become increasingly flamboyant as his wealth grew. Stanford owned jets and yachts. His personal life was also becoming increasingly chaotic. Stanford once told his staff that his priorities were “God, family, and me.” But he ended up separating from his wife and fathering six children with four different women.

Jimmy Davis was the antidote to that apprehension. Having a guy like Jimmy Davis on staff calmed people’s jitters.

Danny Horton, the mayor of Baldwyn, told me, “Mr. Davis was a real asset to our city.” In fact, though Allen Stanford was a Texan, and Houston was Stanford’s headquarters, Davis made the unusual decision to keep his own office in Memphis, in part so he could remain active in Baldwyn’s civic life.

Access to MinistryWatch content is free. However, we hope you will support our work with your prayers and financial gifts. To make a donation, click here.

Mayor Horton said, “Mr. Davis moved back into the same home that had been in his family for generations, and he bought and renovated several buildings here. He had a love and a passion for the rural community.”

Davis even taught Sunday school at Baldwyn’s First Baptist Church, and it was there that a teenager, Laura Pendergest (now Pendergest-Holt), came to his attention. Baldwyn’s Mayor Horton told me she is “a fine young lady from a fine family” who went off to “The W,” which is what locals call the Mississippi University for Women.

“The W” has a reputation for being precisely the place where “a fine young lady from a fine family” would go. For generations, it had been a kind of finishing school for girls from Mississippi’s elite families. The academics are respectable, but not overly rigorous. The tuition was stiff enough to accomplish what the academics could not: keep the neighborhood from going to pot. “The W” had traditionally produced the “perfect professional’s wife.” In recent years it had produced a few top professionals of its own.

One of those would be Laura Pendergest, who pursued a degree in math education at “The W.” She joined Stanford Financial Group soon after graduation. Under the mentorship of Jimmy Davis, her former Sunday school teacher, she rose quickly through ranks. By the time she was thirty, with no specialized financial education except what she was able to pick up on the job, she became the firm’s chief investment officer and occupied an office next to Davis’s in Memphis.

Pendergest-Holt was not a certified public accountant (CPA) nor did she hold the chartered financial analyst (CFA) designation.

David Baglia spent more than 20 years as chair of the department of accounting at Grove City College, a Christian college in Pennsylvania. He later chaired the accounting department at Campbell University. Baglia said, “The requirements for these designations are rigorous, but these designations are fairly common for this level of responsibility. The fact that the chief investment officer at such a large firm didn’t have these designations or other similar designations is unusual.”

Rusty Leonard was more blunt. “It was a recipe for disaster,” said Leonard, himself a CFA who managed money for the legendary investor Sir John Templeton.

The fact that Pendergest-Holt and Davis first met in church was not that unusual for Stanford Financial Group. Religious faith, personal connections, and church ties were common at Stanford. The story about Jimmy Davis having met Laura Pendergest-Holt in church became a part of the oral culture at Stanford Financial Group. Many of Stanford’s employees were recruited as a result of relationships in church or Christian organizations.

In 2005 and 2006, Stanford caused waves in the financial planning industry by bulking up its U.S. network of financial planning offices. In just a few years, Stanford had a network of almost thirty offices, mostly in the Southeast, and more than a hundred advisors. Many of the organization’s leaders were outspoken Christians who recruited other like-minded financial advisors, according to Greg Leekley, who was a consultant to Stanford during the heyday of the recruiting process. “We weren’t trying to set up a Christian financial planning practice,” Leekley told me. “And we weren’t looking for just Christians. But when you know the same people and have the same beliefs, the trust comes more quickly.”

Baglia said that such affinities are not necessarily unusual or improper, but they do sometimes lead to sloppiness in the due diligence process. “We’re comfortable working with people we know and have an affinity with,” Baglia said. “But that does not absolve us of the responsibility of due diligence.”

Anyone looking closely at Stanford might have also been concerned by the nepotism. In part because Jimmy Davis still kept close ties to Baldwyn, Mississippi, nepotism soon developed. Pendergest-Holt’s sister married Ken Weeden, Stanford Financial Group’s former managing director of investments and research. Pendergest-Holt’s cousin Heather Sheppard was an equity specialist.

Further, when the case eventually came to trial, testimony revealed that at different times the “straight arrow” Jimmy Davis was perhaps not so straight. He had maintained affairs with both Heather Sheppard and his protégé Laura Pendergest-Holt.

But most of the information about all these convoluted and sometimes sordid relationships did not become public until much later. While Stanford, Davis, and Pendergest-Holt were building the business, they presented to the world an image of small-town Christian values.

In retrospect, Baglia said, all of these circumstances should have been warning signs. But he said that when you’re on the inside and the money is flowing, human nature makes it tough to call a time-out and ask hard questions. “Our accounting society has a t-shirt that says, ‘In God We Trust. All Others Subject To Audit.’ That’s good advice, even when you’re dealing with Christians.”

Stanford’s “Black Box”

Such advice seems obvious now, but in 2005 this advice was easy to ignore. At Stanford Financial Group, the money was flowing. The main source of revenue was Stanford’s certificate of deposit, or CD.

A certificate of deposit is a common, popular investment vehicle. Most CDs are offered by banks, credit unions, and thrift institutions (often called savings and loan institutions). In many ways they are like a savings account, but with two important differences. When you put money in a savings account, you can put even a very small amount in, and you have immediate access to that money. You can deposit it one day and withdraw it the next.

CDs require you to leave your money in for a set period of time. The minimum amount of time is usually around six months, though one-year CDs are the most popular. Longer-term CDs are also common. For this reason, CDs are sometimes called time deposits. Another difference between CDs and savings accounts is that CDs usually require a minimum investment, often $500 or more. The larger the investment, and the longer you are willing to leave your money untouched, the better the interest rate you will get. So-called jumbo CDs usually require an investment of $100,000 or more.

Because of these qualities, banks are usually able to offer interest rates on CDs that are slightly higher than the rates they offer on their regular savings accounts. Investors and savers who will not need their money for long periods of time, such as those saving for college or retirement (or wealthy people who don’t need their money to live, but don’t want to lose it), like CDs because they give a guaranteed, risk-free rate of return. In fact, if you buy a CD through your local bank, it is treated as a deposit by federal regulators and is insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

So how do the banks make their money? They take the money that is invested in CDs by individual investors and they combine that money and larger investments in financial instruments that offer slightly larger returns, financial instruments that are available only to large investors.

For example, a bank might take $1000 from you and offer you a guarantee of 5 percent interest if you let them keep your money for a year. The banks could then combine your money with the money of many others and make a $100,000 investment in a financial instrument that pays a guaranteed 7 percent interest, but which won’t take small investments from individual investors. At the end of the year, you get your $1000 back, with 5 percent interest. The bank has made only 2 percent, but the bank made it with your money, and the bank is handling millions or billions or – in the case of large financial institutions – hundreds of billions of dollars.

Before Allen Stanford came along, the CD market was one of low risk and small profits. After banks pay their own expenses, they might make as little as 1 percent per year on CD products, but the business is worthwhile because literally trillions of dollars in CDs are bought and sold each year.

Stanford’s CD product was different. At a time when other CDs were offering 6–8 percent, Stanford was promising 10 to 12 percent on its CD product. The Stanford Financial Group said that they were investing in safe and easily sellable (“liquid”) financial instruments, such as government bonds and stock market funds. They said that they were able to offer the higher interest rates because they accepted only large investments. This reduced transaction costs.

Stanford also placed a certain percentage of funds went into what it sometimes called a “black box.” It suggested that the money in the black box produced outsized investment returns without significantly affecting the risk of the overall fund. Stanford maintained that it couldn’t tell investors what was in the black box because that disclosure would destroy its competitive advantage.

This lack of transparency should have been a warning signal. Rusty Leonard said, “With a ‘black box model’ the manager is essentially saying ‘trust us, we know what we are doing.’”

Thousands of investors should have known better. Even more culpable are the hundreds of investment advisors Stanford had recruited. But they all turned a blind eye to the warning signals and focused their eye instead on what the Securities and Exchange Commission later called “improbable, if not impossible” rates of return. Eventually, at least 50,000 investors poured at least $8 billion into Stanford Financial Group’s CD products.

Riding High

With that kind of money flowing in, life was indeed good for Allen Stanford, Laura Pendergest-Holt, and Jimmy Davis. Because Allen Stanford had moved to Antigua to avoid taxes and pursue his newly discovered passion for cricket, many of the day-to-day operations of Stanford were run not from Stanford Financial Group’s headquarters in Houston, but from Jimmy Davis’s office in Memphis. This geographical dislocation further allowed wrongdoing to proceed without oversight and scrutiny.

What most of the organization did not know was that it wasn’t just Stanford himself who was investing in Antiguan real estate or television-friendly cricket match. It later came out that much of the money came from investors in Stanford’s CD products.

The large contingent of evangelical Christians within Stanford also led the company to invest in Christian-themed activities and investments. Stanford invested in a film called The Ultimate Gift, which has a Christian message. The movie eventually turned out to be a good investment for Stanford, costing less than $10 million to produce and market, but eventually generating more than $30 million in revenue, including the DVD sales.

So some investments made from Stanford’s “black box” turned out OK, but others did not, especially after the financial crisis hit in 2008. Billionaire Warren Buffett is reputed to have said, “You don’t know who’s swimming naked until the tide goes out.” It turns out that when the financial tide went out during the Great Recession, Allen Stanford was exposed. The money that individual investors had been pouring into Stanford’s CD products was not being reinvested in safe, liquid instruments. That money was invested in risky and illiquid enterprises.

All of these details about the risky investments and Allen Stanford’s personal life were carefully guarded by the evangelical Christians in Stanford’s organization who used his investments in Christian activities, as well as the Stanford Financial Group’s support of Memphis-based St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital, to project a high-integrity, family-friendly image.

But the fraud complaints and lawsuits started flying in 2009. An amazing story started to unfold.

The Unraveling of Stanford Financial Group

A February 17, 2009, civil complaint first made Stanford’s fraud public. This complaint recounted in detail a February 2009 meeting in an airport hangar in Miami that included three Stanford employees who became cooperating witnesses. These three met with Pendergest-Holt, two unnamed Stanford executives, and an attorney.

Pendergest-Holt revealed to these employees/informants that assets in one portion of Stanford’s portfolio had decreased in value from $850 million to just $350 million in about seven months. At another meeting several days later, one of the soon-to-be cooperating witnesses “broke down crying because of the revelations” and threatened to go to authorities.

The complaint continues: “Soon thereafter, Attorney A walked over to (the confidential informant) and suggested they begin to pray together.”

To add to the drama, on the day the complaint containing this story was made public, Allen Stanford went missing. A nationwide search and a media frenzy ensued. Federal marshals raided Stanford’s offices in Houston and Memphis. The Dallas office of GodTube, one of the Christian businesses in which Stanford had invested, was searched by federal authorities.

Charlotte, which had served as the backdrop for the PTL/Jim and Tammy Bakker scandal a few decades earlier, also played a bit part in the Stanford saga. Stanford Financial Group had an office in Charlotte with more than twenty-five employees, most of whom had recently moved—and brought their clients—from Bank of America, Wachovia, and other Charlotte-based financial institutions. That office was subsequently shut down, throwing those employees out of work.

Also in Charlotte, The Film Foundry, the company that produced The Ultimate Gift, found itself cash starved. Even though its projects with Stanford had been profitable, much of those profits, in the millions of dollars, were held in Stanford accounts that were now frozen by federal authorities.

Sharing the Film Foundry building in Charlotte’s fashionable South End Historic District was the Open Finance Network (OFN), co-founded by Greg Leekley, the man who had helped Stanford recruit Christian financial advisors. Stanford had invested more than $10 million in this technology startup and had pledged millions more. In part because of Stanford’s participation, OFN had ultimately been able to raise more than $25 million in venture capital over a five-year period. The company’s technology was on the verge of being market ready. In fact, it had just started producing revenue. However, it was not producing enough to take care of its more than one hundred employees. With Stanford’s assets now under the control of a federal judge, cash infusions to OFN stopped. Virtually all hundred employees lost their jobs overnight. Stories such as these were played out all across the country.

Authorities eventually found Allen Stanford in Fredericksburg, Virginia, three days later, with his girlfriend. (Stanford was not yet divorced from his wife Susan, whom he married in 1975 and with whom he has a grown daughter. However, they have been separated by this time for more than a decade.) Stanford’s attorneys said he was not fleeing, but had simply “relocated” there with his girlfriend.

According to a press release from the Justice Department issued soon after Stanford was found in Fredericksburg, the case was built with contributions from the FBI’s Houston Field Office, Internal Revenue Service-Criminal Investigations and the U.S. Postal Inspection Service. It was prosecuted by attorneys from the Washington, D.C., Criminal Division’s Fraud Section.

Having this kind of investigative firepower leveled against you is big trouble, not just for Stanford but for Laura Pendergest-Holt and James Davis, those two former pillars of Baldwyn, Mississippi’s First Baptist Church. James Davis originally remained tight lipped in apparent solidarity with his old Baylor roommate. He cited his Fifth Amendment right and refused “to testify or provide an accounting . . . or produce any documents related to the matters set forth in the Commission’s complaint.”

But Pendergest-Holt’s quick ascent from “The W” to a lofty title and a salary of as much as $1 million a year was followed by an equally quick descent. The eminent prospect of trading her pearls and high heels for an orange jumpsuit shocked her into cooperating with authorities. She was arraigned on criminal charges in a Houston court on February 27, 2009, just a week after the first civil lawsuits against Stanford were made public. She was charged with obstructing the government’s investigation of Stanford. Prosecutors had asked for bail to be set at $1 million, but Pendergest-Holt’s attorneys successfully argued that because her assets were frozen, as were the assets of thousands of Stanford investors, that she could not make this bond. It was ultimately set at $300,000, of which she had to produce $30,000. She made bail and was released, though she was required to wear an ankle monitor, a fashion accessory not much in vogue among the polished graduates of the Mississippi College for Women.

These events cracked Laura Pendergest-Holt’s high-gloss veneer. Her attorneys announced a couple of weeks later, in March 2009, that their client is “fully cooperating” with authorities. James Davis, her old mentor, ultimately said he too would cooperate.

Their cooperation lightened their punishment considerably. On June 21, 2012, ten years ago last month, Laura Pendergest-Holt pleaded guilty to obstructing a Securities and Exchange Commission investigation. On September 13, 2012, she was sentenced to three years in prison, followed by three years of supervised probation. She obtained her full freedom on April 23, 2015. On January 22, 2013, Davis was sentenced to five years in jail, to be followed by three years of supervised. He also had a judgment of $1 billion against him. Jimmy Davis left prison on July 24, 2017.

Their cooperation helped investigators build an ironclad case against Allen Stanford. On June 19, 2009, the Justice Department unveiled criminal charges against Stanford and four other officials at his Stanford Financial Group, as well as against Leroy King, administrator of the Financial Services Regulatory Commission in the island nation of Antigua and Barbuda, where the company had its headquarters.

So less than a year after being Number 205 Forbes list, FBI agents took Stanford into custody. He ultimately became prisoner number 35017-183.

But much drama remained before Stanford’s conviction. While in custody, he got into a fight with other prisoners, who beat him severely. His lawyers said the beating had given Stanford amnesia and made him unfit to stand trial. That argument didn’t work, so they said Stanford was addicted to anti-anxiety drugs that impaired his judgment and made him unfit. That worked long enough to get Stanford weaned off the drugs. Stanford’s lawyers used the time to sue the FBI and the Securities and Exchange Commission for $7.2 billion, claiming that it was not Stanford’s fraud and mismanagement that caused billions to vaporize, but the “Gestapo” tactics of federal law enforcement.

While all these machinations delayed proceedings, they could not prevent the inevitable. Finally, on March 6, 2012, after a trial that lasted six weeks, it took the jury only three hours to convict Allen Stanford.

On June 14, 2012, Stanford was sentenced to 110 years in prison. Prosecutors had sought a longer sentence, calling Stanford a “ruthless predator” and someone who “lived a life steeped in deceit.” Unless something extraordinary happens, Allen Stanford (no longer “Sir” Allen Stanford after his knighthood was stripped) will die in prison.

But for many people swindled by Stanford, Davis, and Pendergast-Holt, the prison sentences bring no comfort. A full 10 years later, most of Stanford’s victims had seen little or no money recovered. Angela Shaw’s family lost millions. She told CNBC in 2019, on the 10th anniversary of Stanford’s arrest, “The only true justice Stanford’s victims could ever see is in getting their savings back. Sadly, all they have seen and can expect to see is a few pennies on the dollar.”