Nonprofits Becoming For-Profits: Where are the Lines of Legality?

Experts weigh in on nonprofit to for-profit transitions.

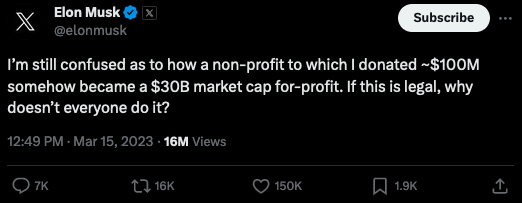

After OpenAI CEO Sam Altman turned his nonprofit research laboratory into a for-profit, one of the organization’s biggest donors asked a compelling question.

Elon Musk, America’s favorite billionaire, wrote, “If this is legal, why doesn’t everyone do it?”

Elon Musk, America’s favorite billionaire, wrote, “If this is legal, why doesn’t everyone do it?”

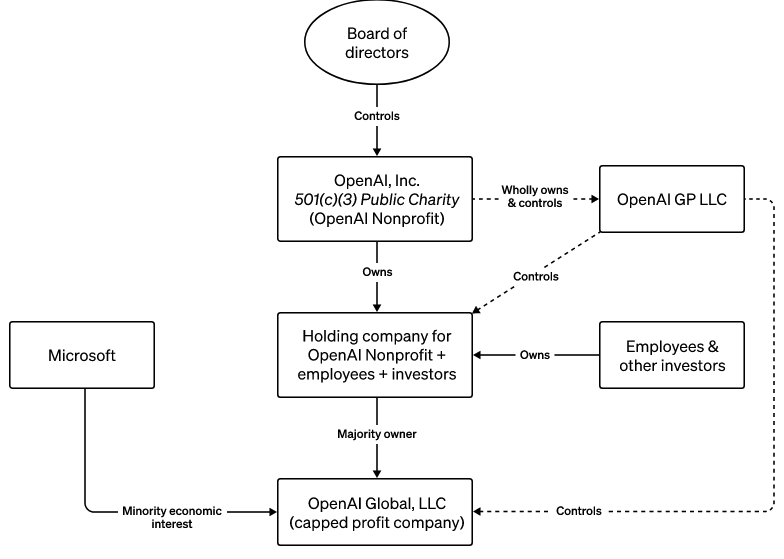

After the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) granted OpenAI 501(c)(3) tax-exempt status in 2016, it amassed $130.5 million in donations under the mission of advancing digital intelligence that benefits humanity while being “unconstrained by a need to generate financial return.” Three years later, executives restructured OpenAI as a hybrid for-profit and nonprofit, unlocking the ability to raise capital. They created a for-profit subsidiary with “a capped-profit” model limiting returns to 100x for the venture’s investors. Anything higher would go to the nonprofit parent, which fully controls the subsidiary.

OpenAI’s formation focused on upholding ethics and transparency in AI through open-source research. These principles, Musk contended, were at odds with the new profit-making structure. Subsequent fundraisers and business deals boosted the company’s value to over $30 billion. It’s now seeking a $100 billion valuation through an upcoming funding round. Also, a recent rule change will increase the profit cap by 20% annually starting in 2025.

OpenAI’s formation focused on upholding ethics and transparency in AI through open-source research. These principles, Musk contended, were at odds with the new profit-making structure. Subsequent fundraisers and business deals boosted the company’s value to over $30 billion. It’s now seeking a $100 billion valuation through an upcoming funding round. Also, a recent rule change will increase the profit cap by 20% annually starting in 2025.

Musk’s legality question could apply to other areas of the nonprofit world, including Christian ministries and organizations. The short answer: Transitioning from a nonprofit to a for-profit — or the reverse — is legal but complicated, involving a lengthy restructuring process, asset distributions, and state approvals.

David Bea, founder and principal of Bea & VandenBerk, cautions that it’s a bit of a misnomer to say a nonprofit can “convert” to a for-profit. The primary way for a tax-exempt nonprofit to become a for-profit (no longer tax-exempt) is to sell all assets, including business activities, to a for-profit in an “arms-length transaction.”

“For this to be legal under federal tax law, the for-profit must pay at least the fair market price for the assets. After the sale, the nonprofit continues to exist, but instead of having assets or ongoing activity, it now has only cash,” Bea says.

After that, the nonprofit would donate the remaining funds to one or more separate 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organizations and dissolve. Distributing remaining assets to another 501(c)(3) is also required of any 501(c)(3) dissolving for other reasons, not having sold its assets.

It’s illegal to sell those assets to insiders with the power to control the nonprofit’s decision to sell unless it’s approved by fully independent board members unrelated to the buyer by blood, marriage, or business relationships.

Sean Kosofsky, owner of Mind the Gap Consulting, has worked with nonprofits and political campaigns for over 30 years. He says rules vary by jurisdiction, but generally, the easiest solution is to dissolve the nonprofit and reincorporate as a corporation. This happens at the state level.

Access to MinistryWatch content is free. However, we hope you will support our work with your prayers and financial gifts. To make a donation, click here.

State attorneys general (AGs) are typically responsible for approving any liquidating distribution. A tax-exempt 501(c)(3) would need to distribute its assets to another 501(c)(3) before changing to a taxable status. This relinquishment is no easy task, according to Baker Hostetler Partner Alexander Reid, who leads the firm’s exempt organizations and charitable giving team.

“Any conversion would require notice to the state AG, who would be called upon to ensure that there is no private inurement (i.e., distribution of net earnings to insiders) or private benefit (direct or substantial economic benefits outside the charitable class ordinarily benefitted by the organization),” Reid says.

Some states are particularly stringent. Bea notes that New York requires nonprofits to obtain the AG’s permission before dissolving or selling all their assets, which “can be lengthy and difficult.” Illinois, on the other hand, doesn’t demand advance approval.

Since AGs have broad powers to protect the public interest, they’ll often request documentation about the reason for the distribution and conduct an audit to review any improper uses of funds before approval. “There are no formal rules, so it is an open-ended inquiry that can end with surprising results,” Reid says. “If the AG finds a tax issue, they’ll often refer it to the IRS for examination.”

While there are ways for nonprofits to dispense their assets in a way that’s in service to their mission, Kosofsky says there’s very little enforcement in this area, leaving broad flexibility in options.

“The nonprofit would either need to return the assets to their donors or find a way to dispense of it in the form of a grant, but converting it to the new corporate model would be difficult but probably possible,” he adds. “Those funds cannot be used as assets to create wealth, but they can be used to pay for attorneys and employees during the transition. Companies don’t have mission statements like nonprofits.”

Two Case Studies

The last few decades have seen many conversions of nonprofit hospitals and schools to for-profits, and vice versa. Grand Canyon University (GCU), a Christian university in Arizona with 117,800 on-campus and online students, is a pertinent example. The school operated as a nonprofit from 1949 to 2004

before becoming a for-profit under a publicly traded parent, Grand Canyon Education (GCE). It then switched back to a nonprofit in 2015, re-securing 501(c)(3) status from the IRS. As part of the $875 million transaction, GCE transferred the campus property to GCU, along with tangible and intangible assets, academic and related operations.

before becoming a for-profit under a publicly traded parent, Grand Canyon Education (GCE). It then switched back to a nonprofit in 2015, re-securing 501(c)(3) status from the IRS. As part of the $875 million transaction, GCE transferred the campus property to GCU, along with tangible and intangible assets, academic and related operations.

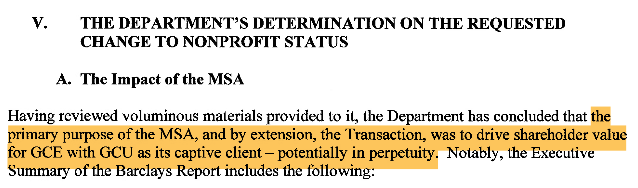

Although the IRS had already approved GCE’s return to a nonprofit, the U.S. Department of Education rejected the application over concerns about its ties with the former owner, GCE. Since 2021, the parties have been in an ongoing court battle. GCU can’t market itself as a nonprofit until the department approves the switch.

The Department of Education flagged a few issues: Though GCU separated from GCE in 2018, the relationship didn’t end there. The pair entered a 15-year master services agreement (MSA) to provide marketing, recruitment and other support in exchange for 60% of the university’s tuition and fee revenue. In a letter explaining why it sees GCE as a for-profit, the department concluded the following:

Shared leadership is another problematic factor, as the university’s president, Brian Mueller, also serves as GCE’s CEO. GCU’s latest Form 990 filing (2021) states Mueller is “employed by and receives compensation for services provided to Grand Canyon Education, Inc., an unrelated organization.”

In 2021, nearly half of GCU’s functional expenses fell under the “other” line item — $784 million out of $1.6 billion total — with a footnote explaining the GCE agreement and education service fees. GCE is also listed as an independent contractor with $820.8 million in compensation.

GCU isn’t the only Christian nonprofit closely intertwined with a for-profit entity. The Inspirational Network, a South Carolina-based Christian media nonprofit, owns several for-profit entities under the same control. The parent raises tens of millions in donor funds each year, including $23.9 million in 2022, while the top executives enjoy sector-leading salaries mainly provided through related organizations. The CEO alone earned over $9 million, nearly all of which came from this category.

According to its latest (2022) Form 990, Inspirational Network Inc. has several subsidiaries — taxable as corporations or trusts — to which it is the direct controlling entity. That includes two C corporations, the largest being a holding company for its broadcasting subsidiaries, with a $260 million share of total income and $768.9 million of end-of-year assets. The other is CrossRidge Master Association, an infrastructure management company with $66,595 in income and $77,545 in assets.

The nonprofit controls four property development firms worth over $42 million. The filing also mentions a $117.2 million investment in an unnamed subsidiary.

The Trinity Foundation dug into the organization’s finances recently, noting the inner-workings are muddy because The Inspirational Network doesn’t publish a consolidated financial statement for the parent and subsidiaries. The ministry reported $308 million in assets in 2022. If combined with the holding company and property development subsidiaries, its total assets would top $1 billion.

We cite these two examples not because they’re breaking any laws necessarily. Rather, they represent the lack of clarity and oversight in tax regulation, which is unequipped for active enforcement.

TO OUR READERS: Do you have a story idea, or do you want to give us feedback about this or any other story? Please email us: [email protected]