Christian Care Homes Struggle to be the Family Their Residents Can’t See

“Mom, it’s me.”

The young woman stood outside Tealridge, an independent living facility in Oklahoma City, and talked to her mother through a window.

But Mom didn’t recognize her.

She tried again.

“See, it’s your daughter,” she said, taking off her mask.

Still, no recognition.

Sitting on a bench under the facility’s portico, Marilyn Dobson watched the interaction—a social distance away but close enough to feel the heartbreak.

“I think that, by the time the conversation was over, she had come around,” Dobson said of the mother, “but it just showed me the damage that has been done emotionally by being isolated the way people have.”

Dobson and her husband, Max, have spent almost every hour of the past eight months at Tealridge, which is associated with Churches of Christ.

Tealridge, like assisted living and senior care facilities across the nation, has operated under strict lockdown and quarantine procedures in the wake of COVID-19. The global pandemic has taken a deadly and disproportionate toll on the elderly. Those with Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias are at increased risk of contracting the virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The threat isn’t only physical, said Sabrina Porter, president of Texas-based Christian Care Communities & Services. In many nursing homes, “the people who are dying are not dying of COVID. They’re dying of loneliness.”

The not-for-profit, founded 73 years ago for retired ministers from Churches of Christ, operates three communities in the Dallas/Fort Worth area. Among the hundreds of seniors it serves is Porter’s 91-year-old mother, whom she hasn’t seen in person since March, abiding by the rules she requires others to follow.

For isolated seniors, phone calls and video visits with family members can help, said Jim MacKenzie, chaplain for the Church of Christ Care Center in Clinton Township, a Detroit suburb. But there’s no substitute for presence and physical contact, both denied by the virus.

“Isolation has hurt us all, really, but maybe on a more profound level with the elderly,” MacKenzie said. “They really cherish those contacts with their loved ones.”

Four Months “I Can Never Get Back”

The lockdowns also have robbed families of precious, critical time with loved ones suffering from progressive memory loss, said Dick Long, a member of the Three Chopt Church of Christ in Richmond, Va.

His wife, Billie Jo, has Alzheimer’s, and in 2014 the couple moved to Richmond to be close to their youngest daughter. That year Billie Jo, “BJ,” moved into a memory care facility.

For four months, Long was unable to visit his wife due to COVID-19 restrictions. He couldn’t talk to her, sing to her, read her Bible to her, pray with her or hug her.

“As a result, BJ’s Alzheimer’s progression has increased significantly,” he said. “She is now in the end-of-life stage.” After multiple appeals, Long was deemed essential to his wife’s care and allowed to reunite with her in early July.

“At the start of our journey with Alzheimer’s, I promised BJ, my sweetheart, that she could always hold on to me,” Long said.

As for the four months they were apart, he said, “That’s something I can never get back.”

Isolation and Regulations

Turning family members away from seeing their loved ones is excruciating, said Matt Mazza, vice president of mission development for Christian Care Communities & Services. In some cases, husbands and wives served by the ministry live in separate buildings because of differing care needs. The lockdowns prevented moving between buildings.

As the restrictions stretched from spring into the hot Texas summer, “we saw the isolation, the disconnect, the separation,” Mazza said. “We saw the regressing of our residents. … We saw their eating habits change significantly, their speaking habits change. Their physical activity level decreased. Everything was decreasing as we were seeing them disconnect from family, friends, which was a real frustration because there was literally nothing we could do about it.”

Serving the elderly is mandated by God, who calls believers to “look after orphans and widows in their distress” in James 1:27, said David Stewart, chief executive officer for the Church of Christ Care Center in Michigan, which includes a 90-bed assisted living facility and a 129-bed nursing home.

“The isolation people feel when they’re placed in a facility like this is real—even when there’s not a pandemic,” Stewart said.

As staffers have worked to address residents’ emotional needs during the lockdown, they’ve had to abide by new rules imposed by the federal agencies that regulate the skilled nursing industry, including the CDC. Michigan’s governor also has issued hundreds of executive orders, many affecting the facility’s visitation and dining policies.

“It’s been overwhelming for us to keep up with,” Stewart said of the myriad regulations. It’s like “drinking from the fire hydrant.”

Long, Hot, Joyful Shifts in PPE

The Church of Christ Care Center endured a COVID-19 outbreak in early April.

“We have lost a lot of people,” said Stewart, who described the pandemic as the most challenging experience he’s faced in his 28-year career in the senior living industry. Michigan’s government lists 90 cases of the virus and 23 deaths among residents at the center.

Stewart said he has endured heartbreaking losses and seen acts of true heroism—from staffers and residents alike—in the past eight months.

“I don’t know how anyone who doesn’t have faith gets through something like this,” he said. “If it weren’t for my faith, I probably would have folded up my tent and gone home.”

In Texas, Christian Care Communities has so far been spared from a large outbreak, Mazza said, but about four months into the pandemic the memory care facility in Mesquite had a few COVID-19 cases among residents and staff.

On a hot Sunday afternoon, Mazza, who had been working from home, strapped on multiple layers of personal protective equipment and went to the facility to help. So did Porter, the ministry’s president, and one of its vice presidents.

The building is kept close to 75 degrees for the residents’ comfort, Mazza said. The heavy gown, face mask and gloves made it feel 15 degrees hotter. Mazza helped disinfect window sills, doorknobs, anything that could be touched. Porter visited with the residents and made sure they were eating.

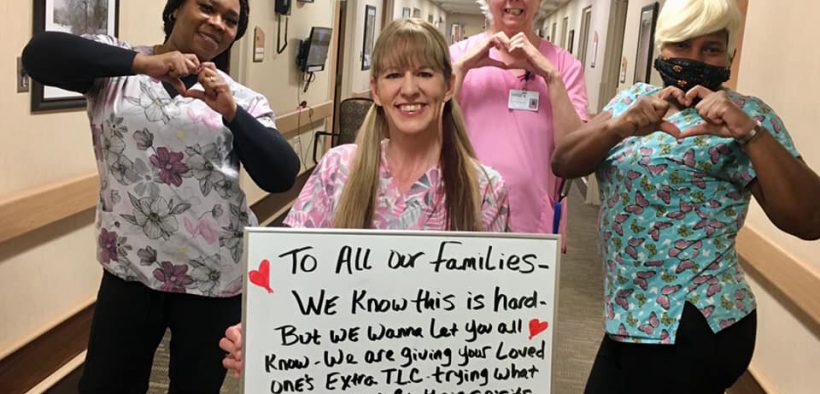

The five-hour experience inspired the staff to launch a “Better Every Day” initiative, encouraging non-nursing staff to volunteer in the facilities, to “be the son, the daughter, the sister, the brother” that the residents weren’t allowed to see.

Mazza has made return visits, going from room to room in full PPE with an iPad and helping residents make FaceTime calls to their families. At the end of his shifts he’s drenched in sweat and full of joy.

As the world outside seemed to boil over—locked down and livid in the wake of racial injustice, violent protests and political debates—the multiethnic team of care workers drew closer through their shared goal of serving the residents, Mazza said.

One teammate told Mazza: “Everything I read online was scary. Everything I came to work and dealt with was scary. I needed something in my life that would provide me with the opposite of that—hope, assurance, confidence and peace. My faith is different today because of what I’ve gone through.”

Another told Mazza that her trust in God has grown, “and not because she expects God to magically heal everything,” he said. She told him: “I trust in God because I don’t have anything else to trust in. He is the only thing I know to trust in, and so I do, more than ever in my life.”

Adversity, Haircuts, and Bingo

Back in Oklahoma, Marilyn Dobson recalled a recent visit by her 8-year-old grandson, George.

Speaking to her through a fence, he said, “Don’t worry, Grandma, I’m gonna get you out of here.”

Restrictions have eased a bit. A hair stylist can now make visits to Tealridge. That may seem like a simple thing, but for both men and women, “that has done something to their soul!” Dobson said.

The facility’s events director has arranged through-the-window concerts by local musicians. “Let Me Call You Sweetheart” is a favorite. The Dobsons also enjoy singing along to, “I’ll be seeing you, in all the old, familiar places…”

There’s also socially distanced bingo, but Marilyn Dobson can’t get her husband to attend.

“You can’t dunk a bingo,” said Max Dobson, who coached basketball and baseball for Oklahoma Christian University.

Tealridge hosts a Sunday communion service, and one resident who attended a Methodist church pre-pandemic told the Dobsons he liked the idea of remembering Christ’s sacrifice weekly.

Marilyn Dobson, age 72, is known as “the kid” among Tealridge’s residents, most of whom are in their 80s and 90s. She spends her days helping where she can and chatting with the facility’s staff, learning their stories.

She’s been reading “Face to Face: Praying the Scriptures for Intimate Worship” by Kenneth Boa and finds strength in the Bible verses the book highlights, including Proverbs 17:17, “A friend loves at all times, and a brother is born for adversity.”

Through the trials of the pandemic and lockdowns, “people are watching us,” Max Dobson said. “I think that’s important to keep in mind.”

In Michigan, chaplain Jim MacKenzie does his best to provide spiritual support for the lonely and isolated souls he serves at the Church of Christ Care Center. Since he can’t lead gatherings of people in prayer, he has initiated daily prayers over the intercom.

“God’s going to show mercy to us, no matter who’s taking care of whom,” he said. “Right now, this is my church.”

This article ran at Religion UnPlugged. Erik Tryggestad is president and CEO of The Christian Chronicle. He has filed stories for the Chronicle from more than 65 nations.